| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sternocleidomastoid | Manubrium Medial third of Clavicle |

Mastoid process Superior nuchal line |

CN XI Accessory n. Cervical plexus C1 - C4 |

Unilateral: I/L cervical sidebend, C/L cervical rotation Bilateral: Head extension, Cervical Flexion, Assists in respiration, Prevents posterior translation during mastication SCJ stabilization |

Sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM)

Anatomy

Overview

The SCM muscle generally has 2 divisions with differing caudal attachments known as the “sternal division/head” and the “clavicular division/head”5. These divisions are separated distally by a triangular space, known as the supraclavicular fossa5.

The SCM is also a landmark that creates the border between the anterior triangle and posterior triangle of the neck5.

Origin

This is considered the distal attachment of the SCM4.

- Sternal head: sternum (manubrium)8

- Clavicular head: Clavicle (medial 1/3)8

Insertion

This is considered the proximal attachment of the SCM4.

- Mastoid process of the Temporal bone8 via a strong tendon5

- Occipital bone (superior nuchal line)8, specifically the lateral half4,5 via a thin aponeurosis5.

Sternal Division

The sternal division refers to the part of the SCM muscle that extends from the sternal head’s origin on the sternum to the head. The sternal division’s fibers are more medial, diagonal, and superficial compared to the clavicular division fibers5. The sternal division extends from the manubrium posterolaterally to the common origin5.

Clavicular Division

The fibers of the clavicular division are more lateral and deep compared to the fibers of the sternal division5. The clavicular division originates from the superior border of the anterior surface of the medial 3rd of the clavicle5. Due to its more lateral origin, the clavicular division fibers ascend almost vertically to the common origin with the sternal div.5.

Variations

The above information is the usual presentation of the SCM, but there are many anatomical variations.

Innervation

The SCM is innervated by CN XI Accessory n., and more specifically the spinal or “external” portion5.

The spinal root of the Accessory n. originates from the anterior horn of the upper ~5-6 cervical segments (C1-C6)5.

The nerve fibers exit the cervical segments and form a trunk5.

The Accessory n. most commonly travels through the two heads of the SCM muscle but has been observed to travel between the two heads5. It is at this region where the accessory n. merges with fibers from C2-C4 nerve roots5. Next, the nerve travels obliquely through the posterior triangle to the deep cervical fascia and trapezius muscles, travelling within a fat layer between the superficial trapezius and deeper levator scapulae5.

Motor

CN XI Accessory n. supplies motor innervation to the SCM in most cases5,8.

Although C2, C3, and sometimes C4 nerve roots may supply the SCM with motor innervation and not just sensation5,8.

Some sources claim that the SCM is predominantly innervated by C1 and C29.

While other sources claim that the SCM is innervated by C2, C3, C4 spinal nerve roots8.

The Accessory n. supplies motor innervation to the SCM in most cases, but variations of SCM innervation include: hypoglossal nerve, ansa cervicalis, facial nerve, and aberrant rami of the transverse cervical nerve5.

Sensory

C2, C3, and sometimes C4 nerve roots supply sensory and potentially motor innervation to the SCM5,8. The ventral rami of these nerve roots supply mainly proprioceptive sensation to the muscle5.

“The second, third, and sometimes the fourth cervical spinal nerves of the ventral rami also enter the muscle.1 It is thought that the C2-C4 connections carry sensory (mostly proprioceptive) information.1 Contrary to this thought, electromyographic15,17 and histochemical17 data show that the nerves have both sensory and motor functions.”5

Vascularization

Since the SCM is a large muscle for the cervical region, it’s vascularization changes based on location.

Upper portion

Branches of the occipital artery and posterior auricular artery supply the upper portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle5.

Middle

The superior thyroid artery supplies the middle portion of the SCM muscle belly5.

Lower

The lower portion of the SCM muscle belly is supplied by the suprascapular artery5.

Action

Since the SCM has 2 distinct heads, each head has a different direction of pull, and could be classified as “cruciate” and slightly “spiralizer”5.

The SCM serves as an active stabilizer of the sternoclavicular joint1

Unilateral Contraction

The SCM works unilaterally to create ipsilateral sidebend of the cervical spine1,4,8 and contralateral rotation of the cervical spine1,4,8.

When combined, this produces an upward sideways glance5.

Bilateral Contraction

Bilateral contraction of the SCM results in extension of the head and upper cervical spine1,8 and simultaneous flexion of the mid-to-lower cervical spine1,4. This seeming contradiction is explained here.

In the sagittal plane, the bilateral SCM contraction results in head and upper cervical extension and mid-lower cervical flexion, but its actions have much more nuance and complexity. When in upright, the SCM work bilaterally to bring the head forward and assist the longus colli to flex the mid-lower cervical spine5. When in supine, the SCM muscles contract bilaterally to lift the flex the head against gravity5. When gazing upwards, the SCM muscles function eccentrically and isometrically to control hyperextension of the neck5.

When the head is fixed, the SCM muscles function as accessory muscles of respiration4,8 to assist in thorax elevation during forced inspiration5.

The SCM also functions to control translation of the head. The SCM also minimizes trauma by resisting forceful posterior translation of the head, including car accidents involving collision from the rear5. Both SCM are coactivated with mandibular movements and work to prevent/control posterior translation of the head during mastication4.

The coactivation of the SCM during chewing and swallowing may play a role in spatial orientation, weight perception, and motor coordination5

Functional unit

The functional unit refers to the muscles that reinforce (synergists) and counter (antagonists) the muscle’s actions5. The organization and neural connections of the sensory motor cortex illustrate the functional interdependence of these structures as a cohesive unit5.

The functional unit is clinically relevant since the presence of a trigger point (TrP) in one muscle of the unit increases the probability that TrPs will develop in other muscles of the unit5. In addition, when treating TrPs in a muscle, the TrPs may then develop in other muscles of the functional unit5.

Biomechanics

Sagittal plane contradiction

The SCM seems to have contradictory actions in the sagittal plane since it performs both

Below ~C3, the SCM crosses anterior to the medial-lateral axes of rotation1. Above C3, the SCM crosses just posterior to the medial-lateral axes of rotation1. As a result, this creates a strong flexion torque to the mid and lower cervical spine as well as a slight extension torque to the upper cervical spine1.

Torque

The lever arm and resulting torque created by the SCM is greatly affected by the posture of the craniocervical region1.

Based on computer modeling…1

When the mid-to-lower cervical spine is flexed, the moment arm doubles the resultant torque1.

This increase in torque with mid-lower cervical flexion plays a major role in the perpetuation and worsening of forward head posture1.

Clinical significance

Control of upright posture is possible through constant interaction between the visual and vestibular system with short range rotators including obliquus capitis posterior inferior, rectus capitis posterior major, splenius capitis, and SCM2.

Muscle groups

The sternocleidomastoid is part of the Superficial neck muscle group

Palpation

Before palpating the SCM, you must first find these landmarks:

Palpate the C1 transverse process gently since this area may be quite tender4.

Now we can begin palpating the SCM.

- Position the patient in supine4.

- Begin at the mastoid process4.

- Since the mastoid process is the insertion of the SCM, you should be able to palpate the thicker proximal part of the muscle4.

- Place your index finger on the medial border, your ring (4th) finger on the lateral border, and your middle (3rd) finger on the muscle belly4. Follow the SCM anterior and inferiorly to its origin on the manubrium and the clavicle4.

Now that we have found and traced the muscle belly, we need to differentiate between the sternal and clavicular heads of the SCM The sternal head is said to be “thin” and “cord-like” near the origin at the manubrium4. The clavicular head is described as “broad” and “flat” at its origin on the clavicle4.

Move the head into extension and cervical contralateral rotation to help differentiate between the sternal head and clavicular head4.

It should be noted that the SCM and the upper trapezius share a continuous attachment along the base of the occiput. At the mastoid process, these two muscles split and have a noncontinuous attachment along the superior border of the clavicle4.

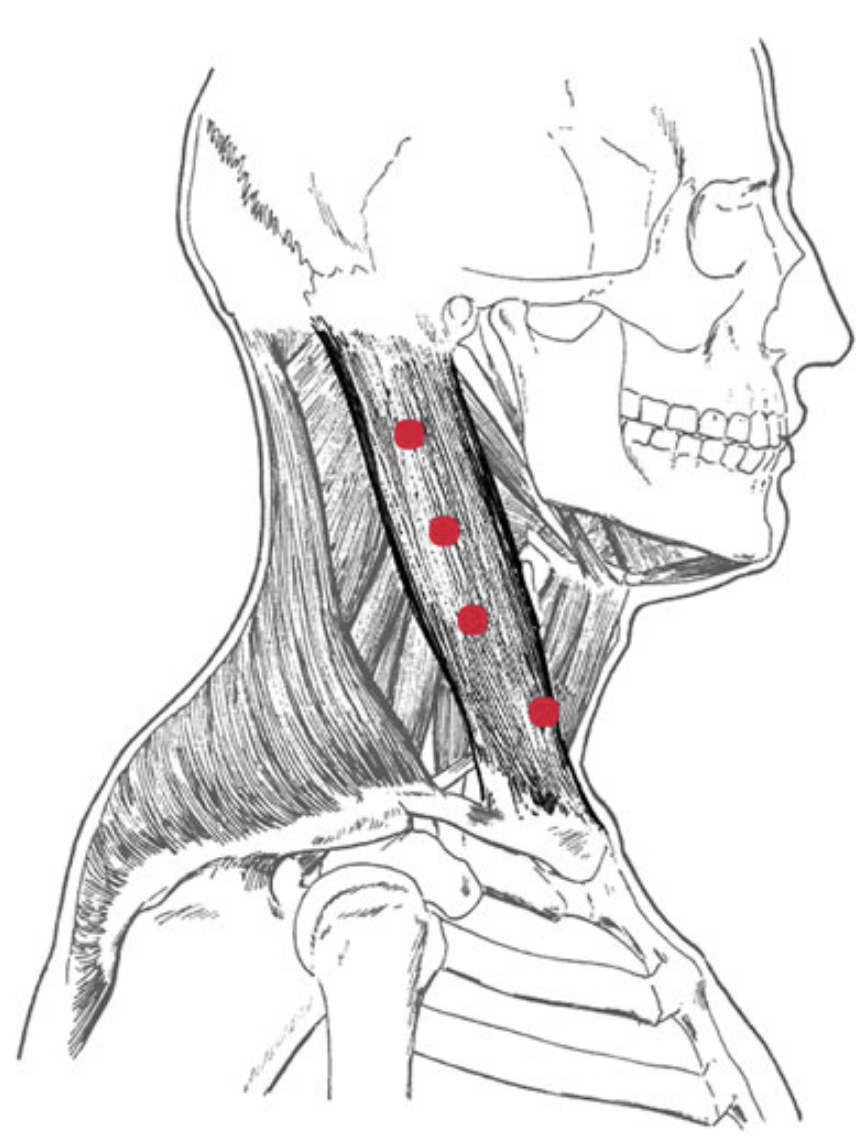

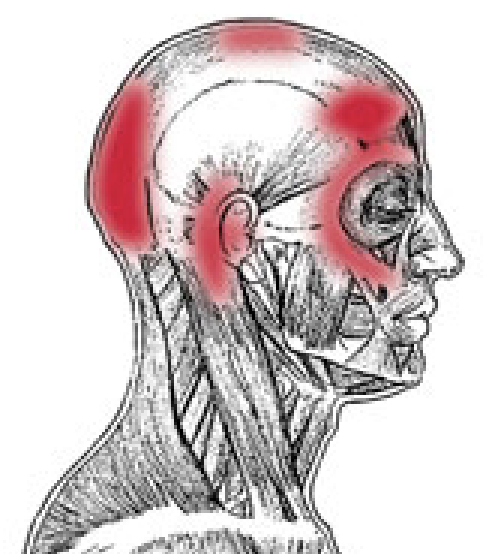

Trigger Points

Pain Patterns

The SCM has 2 distinct pain patterns that are attributed to dysfunction related to the sternal or clavicular head.

Clavicular head pattern

Sternal Head

Pain

Etiology

Common causes of SCM dysfunction include:

Satellite Trigger points

When a patient presents with SCM dysfunction and trigger points, it is common to see these muscles to have associated “satellite trigger points”:

Affected Organ Systems

SCM dysfunction is often associated with respiratory system problems including the eyes, ears, throat, and nasal sinuses4.

Associated Zones, Meridians, & Points

According to Finando4 Certain zones, meridians, and points are associated with SCM dysfunction:

Manual Muscle Test

Unilateral

Position the patient in supine with the head ipsilaterally rotated 45°3.

Instruct the patient: “Don’t let me move you” to cue for an isometric hold.

Apply a downwards pressure at the side of the forehead3.

This will create an ipsilateral cervical rotation and cervical extension moment and will bias the SCM to resist this moment.

Core: Cervical

Antagonist: Neck extensors

Synergist: Abdominal muscles, Iliopsoas muscles, hip flexors

Bilateral

Stretches

- Contralateral sidebend

- Ipsilateral rotation

Since the sternal and clavicular heads of the SCM can have isolated dysfunction, it is important to understand how to bias each head when stretching.

Strengthening

Progressions

- Gravity-eliminated (upright) position with manual isometric resistance

- Against gravity (Supine)

Sagittal plane

The SCM is multi-joint muscle when you look at each cervical vertebrae as an individual joint. Thus, when training the SCM in the sagittal plane (e.g. supine neck flexion), you can bias the SCM by performing cervical flexion while keeping the occiput (C0-C1) in extension. This will place the muscle in a more shortened position, making it less efficient and requiring more recruitment to complete the movement.

Cues

To effectively bias, the SCM we need to recruit it in all 3 planes of motion. Bringing the insertion closer to the origin will achieve that. A good cue I use is “touch the back of your ear to your collarbone.”

Exercises

Isometric against mild forward resistance

- Gently place the palm on the forehead

- Instruct the patient “do not let me move you”

- Have the patient clasp their hands behind their head just below the crown and have the patient press their neck against the resistance of the hands4

Supine Dynamic neck flexion with rotation

- Place the patient in hooklying

- Have them bring their head up and look at their contralateral foot.

- This will create neck flexion with contralateral rotation