Low back MSK

Musculoskeletal Overview

Joints

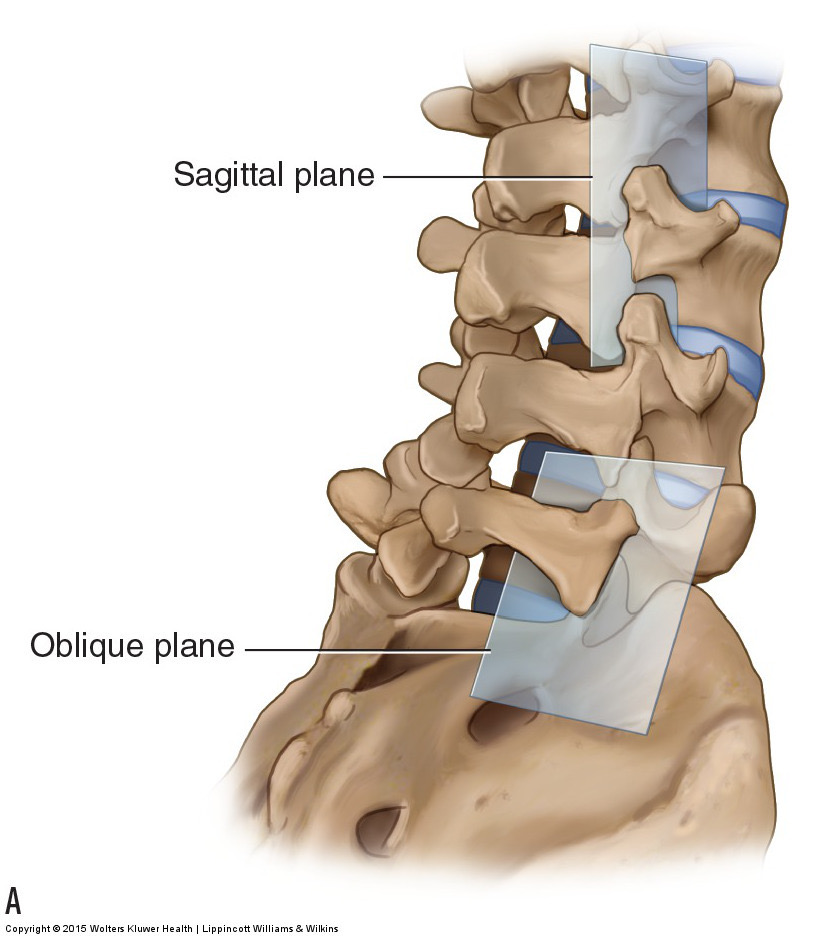

Apophyseal Joints

- ~25° from sagittal plane

- Inferior articular processes

- Convex

- Oriented Ant/Lat

- Superior articular processes

- Concave

- Oriented Post/Med

- L5-S1 apophyseal joints oriented closer to frontal plane

Lumbosacral Junction

Muscles

Segmental Muscles

- Interspinalis and Intertransversarii makeup the segmental muscles grouping which are the deepest intrinsic muscles of the posterior trunk2.

Lumbar Stabilization

“Muscle activity is available and required in the lumbar spine throughout the ROM, except in specific situations, such as at the end of lumbar flexion ROM when a reflex reduction in paraspinal muscle activity occurs, the so-called “flexion relaxation phenomenon.”32,41,42 At the end of spinal ROM, the restraints to bending, rotation, and shear forces are provided largely by tension and compression on the spine’s passive structures. Mobilizer muscles, which tend to work over two joints or several segments, are superficial, and have narrow insertions with long tendons.43 The mobilizer muscles function to produce movement in the sagittal plane using concentric acceleration and are capable of generating a tremendous amount of force (see Chapter 22). The stabilizer muscles, as their name suggests, provide stabilization, and can be either local or global (see Chapter 22). The local muscle system is important for the provision of segmental control to the spine and provides an important stiffening effect on the lumbar spine, thereby enhancing its dynamic stability. The local stabilizers also function to maintain a continuous low-force activity at joints in all positions and directions and thus provide segmental joint support.”3

Theories of Spine Stabilization

Bracing Mechanism

McGill proposed the “Bracing mechanism” (of spinal stabilization), which hypothesizes that

“muscles act similar to guy wires when stabilizing the spine and that a loss of tension can result in unstable buckling of the spinal structures. The muscles of the trunk function via a complex interaction of agonist/antagonist spinal muscles, both segmentally and regionally to provide tension (active stiffness). According to this theory lightly pretensioning, or bracing, the abdominal muscles using an isometric contraction is a way to enhance the guy wire affect by taking up the slack prior to activities that may destabilize the spine.46 The external oblique, IO, and TrA overlay each other to create the abdominal wall and act through attachments to the abdominal and TLF to create a cylinder. As the intra-abdominal pressure increases, the three-dimensional force per unit area exerted on the spine also increases, potentially constraining spinal movement in all directions.”3

Deep Corset Mechanism

Proposed by Richardson

“Richardson et al.45 have proposed that a pressure corset is formed by the muscles of the lumbar spine. Under this proposal, the TrA forms the wall of the cylinder, and the muscles of the pelvic floor and diaphragm form the base and lid, respectively. Within this system, the intra-abdominal pressure group is maintained at a level that provides spinal support. Since the abdominal cavity has a finite volume, the intra-abdominal pressure (force/area) will increase if the abdominal cavity volume is reduced (contraction of the muscles in the pelvic floor, abdominal muscles and diaphragm, and the wearing of a lumbar corset) In addition, the increase in intra-abdominal pressure is thought to provide a mild distractive force to the spinal segments, due to separation of the pelvic floor and diaphragm. Because intra-abdominal pressure and fascial tension are important for the control of intervertebral motion, the muscles that surround the abdominal cavity, such as the diaphragm and the pelvic floor muscles (see Chapter 29), provide an additional contribution. These two muscle groups also have important respiratory and continence functions. Theoretically, reduced contribution of the diaphragm to spinal stability may occur during periods of increased respiratory demand. As the diaphragm descends during inspiration, intra-abdominal pressure increases provided that the musculature of the abdominal and pelvic floor maintains its respective tension.”3

ROM

Lumbar ROM

- 3 degrees of freedom:

- Sagittal: ~65°

- Frontal: ~30°

- Transverse: 10°

- Rotation and lateral bending are coupled contralaterally