Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a loosely fitting articulation formed between the mandibular condyle and the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone1

- Synovial joint

- Motion: Allows wide range of rotation as well as translation.

Joint Structure

- The disc separates the joint into two synovial joint cavities1.

- The inferior joint cavity is between the inferior aspect of the disc and the mandibular condyle1.

- The larger superior joint cavity is between the superior surface of the disc and the segment of bone formed by the mandibular fossa and the articular eminence.

Biomechanics

- Convex: Mandible head

- Concave: Mandibular fossa of temporal bone

When the mandible moves on the mandibular fossa:

- Depression (Opening mouth): Posterior roll + Anterior slide

- Perform a anterior glide to assist with this motion

- Elevation (Closing mouth): Anterior roll + Posterior slide

- Perform an posterior glide to assist with this motion

- Protrusion: Mandibular condyle and disc translate anteriorly

- Retrusion: Mandibular condyle and disc translate posteriorly

- Lateral excursion: In Left lateral excusrion the L condyle forms a pivot point that the R condyle rotates anteriorly & medially

Osteokinematics Overview:

The primary osteokinematics of the mandible are most often described as protrusion and retrusion, lateral excursion, and depression and elevation1.

With all primary movements, there are varying degrees of combined mandibular translation and rotation1. These combined kinematics optimize the mechanical process of mastication.

textbook by Okeson.

Arthrokinematics Overview:

Movement of the mandible typically involves bilateral action of the TMJs. Abnormal function in one joint naturally interferes with the function of the other. Similar to the osteokinematics, the arthrokinematics of the TMJ normally involve a combination of rotation and translation.6 In general, during rotational movement the mandibular condyle rotates relative to the inferior surface of the disc, and during translational movement the mandibular condyle and disc slide essentially together.77 The disc usually moves in the direction of the translating condyle.

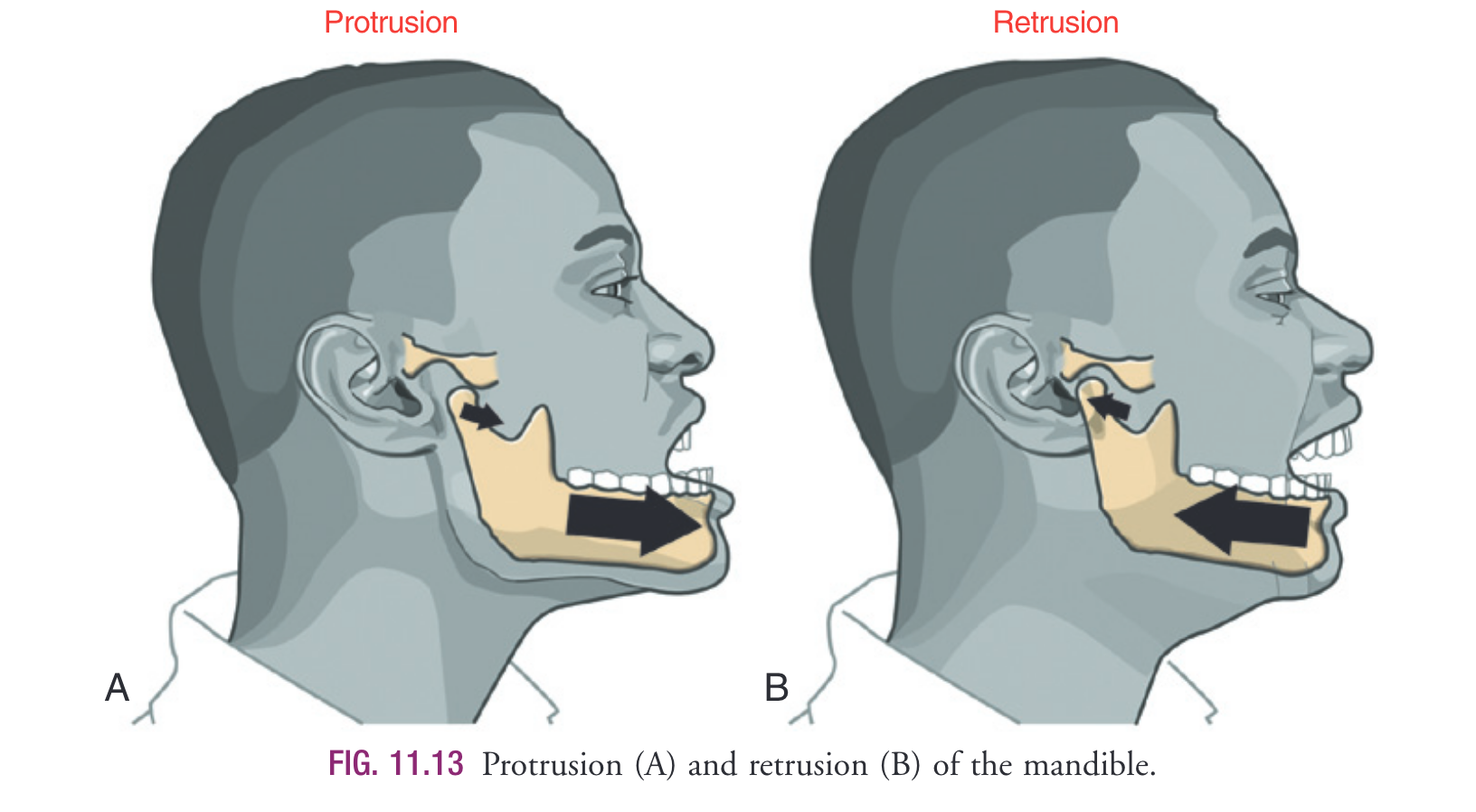

Protrusion/retrusion:

Osteokinematics:

Protrusion of the mandible occurs as it translates anteriorly without significant rotation (see Fig. 11.13A). Retrusion of the mandible occurs in the reverse direction (see Fig. 11.13B). As will be described ahead, protrusion and retrusion are fundamental components of full opening and closing of the mouth, respectively.

Arthrokinematics:

- “During protrusion and retrusion the mandibular condyle and disc translate anteriorly and posteriorly, respectively, relative to the fossa (see Fig. 11.13). Maximum condylar translation of about 1.25 cm (about 12 inch) has been measured in each direction in healthy adults.8 The condyle and disc follow the downward slope of the articular eminence. The mandible slides slightly downward during protrusion and slightly upward during retrusion. The path and extent of the movement usually vary depending on the degree of opening and closing of the mouth (described ahead).”1

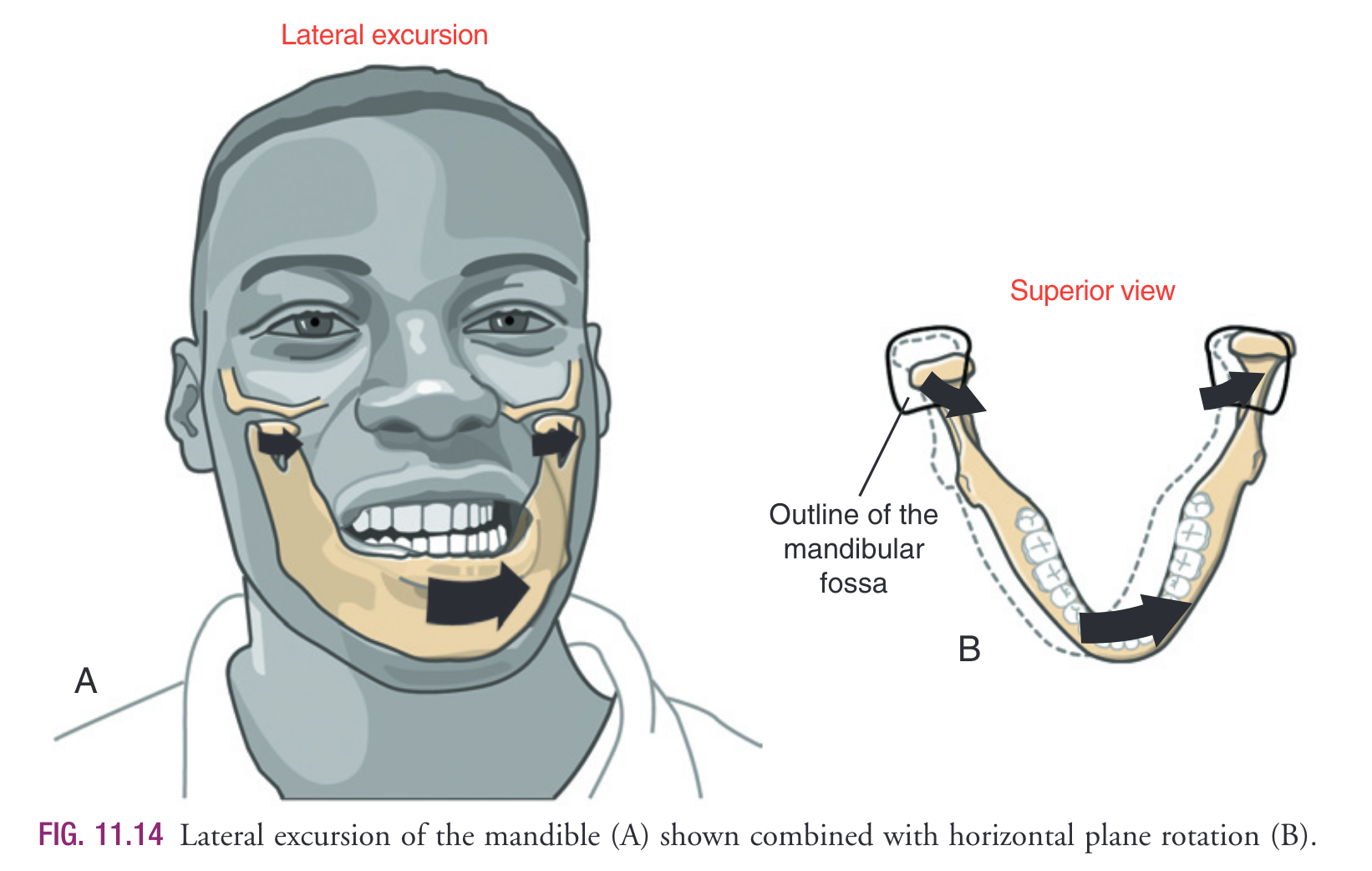

Lateral excursion

Osteokinematics:

- Lateral excursion refers to the side-to-side translation (primarily) of the mandible on the temporal bone1

- The direction of this side-to-side movement is described as contralateral or ipsilateral relative to the side of primary muscle action (right or left)1

- ROM: average adult has 11mm

- In the adult, an average of 11 mm (~\(\frac{1}{2}\) inch)1

Combined movements:

- Lateral excursion is combined with relatively slight rotational movements guided by several factors:1

- Occulsion (Contact made between upper and lower teeth)

- Action of the muscles

- Shape of the mandibular fossa and mandibular condyle, and position of the articular disc. For purposes of evaluating dental occlusion, dentists frequently refer to the side of the lateral excursion movement as the “working” side of the mandible.”1

Arthrokinematics

“Lateral excursion involves primarily a side-to-side translation of the condyle and disc within the fossa. Slight multiplanar rotations are typically combined with lateral excursion. For example, Fig. 11.14B shows lateral excursion combined with a slight horizontal plane rotation. The mandibular condyle on the side of the lateral excursion serves as a relatively fixed pivot point, allowing a slightly wider arc of rotation by the contralateral condyle.”1

Depression & Elevation

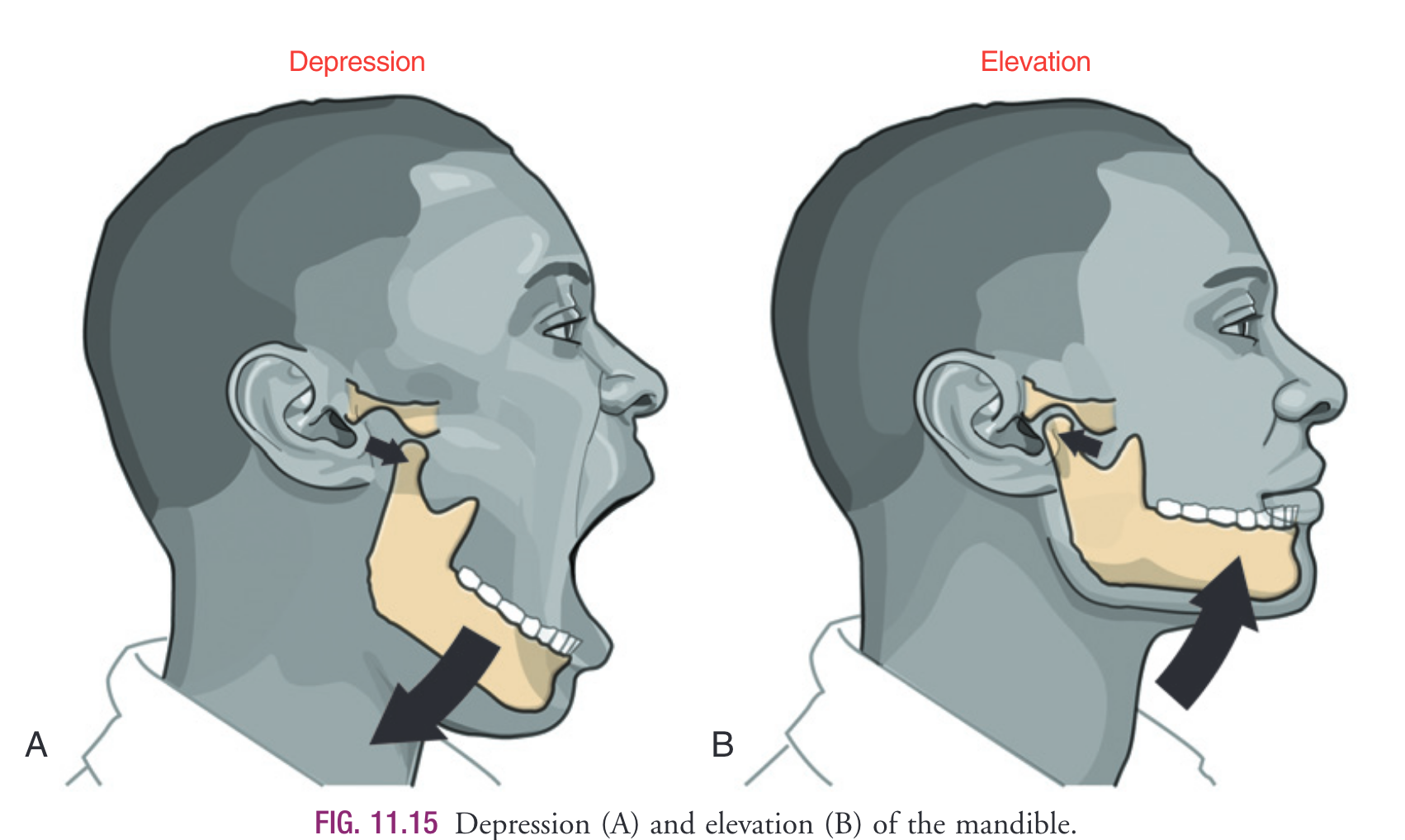

Osteokinematics:

- “Depression of the mandible causes the mouth to open, a fundamental component of chewing (see Fig. 11.15A). Maximal opening of the mouth typically occurs during actions such as yawning and singing. In the adult the mouth can be opened an average of 45–50 mm as measured between the incisal edges of the upper and lower front teeth.18,43,97 T he interincisal opening is typically large enough to fit three adult “knuckles” (proximal interphalangeal joints). Typical mastication, however, requires an average maximal opening of 18 mm—about 38% of maximum (sufficient to accept one adult knuckle). Being unable to fit two knuckles between the edges of the upper and lower incisors is usually considered abnormal in the average sized adult. Elevation of the mandible closes the mouth—an action used to crush food during mastication (see Fig. 11.15B). During this process, the teeth within the elevating mandible strongly oppose the teeth within the fixed maxilla.”

Arthrokinematics:

“Opening and closing of the mouth occur by depression and elevation of the mandible, respectively. During these movements, each TMJ experiences a combination of rotation and translation among the mandibular condyle, articular disc, and fossa. No other joint in the body experiences such a large proportion of translation and rotation. These complex arthrokinematics are a necessary mechanical component of mastication (grinding and crushing of food) and for speaking. Because rotation and translation occur simultaneously, the axis of rotation is constantly moving. In the ideal case the movements within both TMJs result in a maximal range of mouth opening with minimal stress placed on the articular surfaces.”

- Early phase:

- first 35-50% of ROM1

“The early phase, constituting the first 35% to 50% of the range of motion, involves primarily rotation of the mandible relative to the cranium. As depicted in Fig. 11.16A, the condyle rolls posteriorly within the concave inferior surface of the disc. (The direction of the roll is described relative to the rotation of a point on the ramus of the mandible.) The rolling motion swings the body of the mandible inferiorly and posteriorly. The axis of rotation for this motion is not fixed but migrates within the vicinity of the mandibular neck and condyle.32,77,83 The rolling motion of the condyle stretches the oblique portion of the lateral ligament, which may help initiate the late phase of opening the mouth”

It is likely not possible to define a single rotation-to-translation kinematic of the TMJ during opening/closing due to natural intersubject variability in movement strategy and on overall cranial-dental anatomy1

“The late phase of opening the mouth consists of the final 50% to 65% of the total range of motion. This phase is marked by a gradual transition from primary rotation to primary translation. This transition can be readily appreciated by palpating the condyle of the mandible during the full opening of the mouth. The full amount of translation is large, about 1.5 to 2 cm in the adult.18,66 During the translation, the condyle and disc slide together in a forward and inferior direction against the slope of the articular eminence (see Fig. 11.16B). At the end of opening, the axis of rotation shifts inferiorly. The exact point of the axis is difficult to define because it depends on the person’s unique rotation-totranslation ratio. At the later phase of opening, the axis is usually located below the neck of the mandible.Full opening of the mouth maximally stretches and pulls the disc anteriorly. The extent of the forward translation (protrusion) is limited, in part, by tension in the stretched, elastic superior retrodiscal lamina. The intermediate region of the disc translates forward while remaining between the superior aspect of the condyle and the articular eminence. This placement of the disc maximizes joint congruency and reduces intra-articular stress

The arthrokinematics of closing the mouth occur in the reverse order of that described for opening. When the mouth is fully opened and prepared to close, tension in the superior retrodiscal lamina starts to retract the disc, helping to initiate the early translational phase of closing. The later phase is dominated by rotation of the condyle within the concavity of the disc, terminated when contact is made between the upper and lower teeth.”

Articular disc

An articular disc cushions the potentially large and repetitive forces inherent to mastication1.

Capsular pattern

With a capsular restriction, the TMJ would have difficulty with depression (mouth opening).